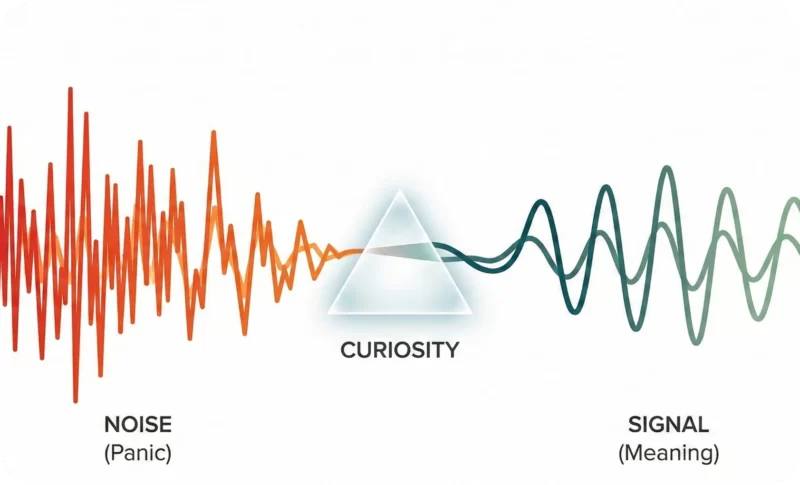

Anxiety is one of the most common human experiences and one of the most misunderstood. Most people hope therapy will help them get rid of anxiety. But what if anxiety as a signal isn’t simply a problem to eliminate, but a meaningful message that something in your life, body, or relationships needs attention, comfort, and care?

Anxiety as a Signal

Therapy for Anxiety

Acceptance-based Skills

Want support with anxiety right now?

If anxiety is interfering with your life, you can explore the GoodTherapy directory to find a clinician who fits your needs: find a therapist near you.

In clinical practice and empirical research, anxiety is understood not just as distress but as a complex biopsychosocial response that tells a deeper story about how a person is experiencing safety, loss, connection, and threat. It reflects dynamic interactions between mind, body, and life circumstances that deserve compassionate understanding, not avoidance. For an overview of how anxiety is defined and experienced, see the American Psychological Association’s anxiety resource.

Key idea: When we treat anxiety as a signal, we shift from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What is my system trying to protect, and what does it need?”

Anxiety as a Signal: More Than a Symptom

The American Psychological Association (APA) describes anxiety as feelings of worry, tension, and physiological arousal that prepare a person for potential threat. While anxiety can become overwhelming or distressing, it is also a normal adaptive reaction in many settings, alerting us to danger, motivating preparation, and facilitating problem-solving.

This adaptive potential suggests a departure from viewing anxiety solely as pathology. Instead, anxiety as a signal can be understood as meaningful internal communication, signalling what has been experienced as unsafe, unresolved, uncertain, or emotionally unmet.

If anxiety is impacting your relationships…

GoodTherapy has a helpful read on how anxiety can disrupt connection, and how to respond with more clarity: anxiety and relationships.

Anxiety and Emotional Loss

Anxiety is often rooted in anticipatory fear, the nervous system’s attempt to protect against unknown or painful experiences. Research commonly conceptualizes anxiety as a future-oriented state tied to anticipation and preparation for what may happen next (see, for example, Craske et al., 2017).

In clinical settings, many people with anxiety also struggle with unacknowledged loss, loss of identity, relationship changes, unmet needs, changes in health, or life transitions that have not been fully felt. When these losses go unexplored, the nervous system can stay activated, producing persistent vigilance and distress.

Therapeutically, when we begin to hold and explore these experiences with empathy, anxiety as a signal can lose its grip as a threat alarm and become a gateway to healing.

What anxiety might be protecting

- Connection you fear losing

- A role or identity that’s shifting

- Unmet needs you learned to ignore

- Grief you haven’t had room to feel

What to try (gently)

- Name the feeling (“This is anxiety.”)

- Locate it in the body (tight chest? restless legs?)

- Ask: “What feels threatened right now?”

- Ask: “What would help me feel 5% safer?”

If loss is part of your story, you may appreciate this GoodTherapy piece on how grief can show up physically, and sometimes overlap with anxiety: the physical effects of grief.

The Body and the Nervous System in Anxiety

Anxiety is not “just in your head.” It is deeply embodied and reflects how your nervous system has adapted to past and present experiences. Research consistently shows that anxiety activates physiological systems, heart rate, breathing, muscle tension, and vigilance, designed to protect the organism from danger (see, for example, Stein & Sareen, 2015).

This embodied aspect offers a powerful direction for therapy: instead of trying to control or suppress symptoms, therapeutic work often focuses on understanding and co-regulating the body’s signals. In this way, anxiety as a signal becomes a relational process between internal experience and external support.

A 60-second grounding reset (not a cure, just a reset)

-

Exhale first (a longer out-breath can soften arousal).

-

Place a hand on your chest or belly, wherever feels supportive.

-

Look around and name 5 neutral objects you can see.

-

Ask: “If anxiety as a signal had a message, what would it want me to notice?”

Anxiety in the Context of Relationships

Human beings are relational by nature. Anxiety often arises in the context of relationship experiences, attachment history, interpersonal losses, uncertainty in connection, or ongoing interpersonal stressors. One consistent finding across psychotherapy research is that the quality of the therapeutic alliance is strongly linked to outcomes (see Wampold & Imel, 2015).

This aligns with what many clients report: anxiety often decreases when they feel genuinely heard, reflected, and cared for, a process that cannot be reduced to “techniques” alone but requires authentic engagement.

If you’d like a clear definition of what we mean by “alliance,” GoodTherapy’s PsychPedia entry is a great starting point: therapeutic relationship (therapeutic alliance).

Prefer skills + insight?

Many people benefit from a blend of approaches. You can explore therapy types and therapist specialties using the GoodTherapy directory.

What the Evidence Says About Effective Treatment

Clinical research recognizes multiple empirically supported treatments for anxiety, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance-based approaches, and psychodynamic therapies.

While CBT remains the most widely studied and traditionally recommended psychotherapy for anxiety (see Hofmann et al., 2012), research also supports the efficacy of relational and insight-oriented therapies that attend to underlying emotional experience and meaning (see Leichsenring et al., 2017).

Two evidence-based paths (often combined)

-

CBT-style approaches: Reduce avoidance and shift threat appraisal, often helpful when anxiety feels “loud” and repetitive.

-

Relational/psychodynamic approaches: Explore how anxiety as a signal connects to attachment history, conflict, loss, and meaning.

GoodTherapy also has a practical overview of CBT and anxiety here: CBT (and relaxation) for anxiety. Acceptance-based models can be especially helpful when you notice that fighting anxiety intensifies it. If you want to learn more about how avoidance can keep anxiety going, see: cognitive avoidance and acceptance-based behavioral therapy.

Anxiety as a Signal: An Invitation to Connection and Self-Understanding

When clients begin therapy, many feel overwhelmed by anxiety, yet at deeper levels, this emotional energy points toward what matters most. Anxiety as a signal often marks domains of life where a person:

- Fears loss of safety or connection

- Holds unprocessed grief or unmet attachment needs

- Has learned to anticipate threat based on past experiences

- Struggles to trust themselves or others with vulnerability

These experiences are not pathological weaknesses; they are meaningful emotional responses to life events that deserve recognition. When you shift your orientation from fighting anxiety to listening to anxiety, healing begins.

Sometimes anxiety as a signal was learned early, especially when caregivers were also overwhelmed. This GoodTherapy article describes how anxiety can function like a protective “alert system” in families: whose anxiety is it, anyway?

Therapy as a Place of Comfort and Exploration

Therapy offers more than symptom reduction. It offers a space where anxiety can be understood, held, and transformed. Instead of avoiding discomfort, we gradually build the capacity to sit with it, understand its origin, and learn new ways of relating to internal experience.

Together, we can explore:

- What your anxiety may be asking you to notice

- How past experiences shape present responses

- What relational patterns may contribute to distress

- Ways to tend to loss, unmet needs, and vulnerability

- How to cultivate deeper self-compassion and resilience

Looking for treatment options?

For general clinical guidance on anxiety treatment, you can review trusted overviews from NIMH, Harvard Health, or Mayo Clinic.

Putting Research Into Practice

Evidence supports that psychological treatments are effective for anxiety, and that the quality of connection between therapist and client plays a central role in outcomes. My approach integrates evidence-based techniques with relational depth, recognizing that anxiety as a signal is not merely something to suppress, but something to understand and transform.

An Invitation

If anxiety has been a persistent companion, interfering with your relationships, daily function, or sense of peace, I want you to know that your experience is valid, meaningful, and worthy of care. You do not have to navigate it alone.

Therapy is a space where your anxiety can be listened to with empathy, your history honoured with nuance, and your inner life gently supported toward healing.

References

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Anxiety

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults

- Craske, M. G., Stein, M. B., Eley, T. C., Milad, M. R., Holmes, E. A., Rapee, R. M., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2017). Anxiety disorders. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3, 17024. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.24

- Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L., & Krone, C. R. (2019). Nurturing nature: How brain development is inherently social and emotional, and what this means for education. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1633924

- Leichsenring, F., Abbass, A, Hilsenroth, M. J., Leweke, F., Luyten, P., Munder, T., Rabung, S., & Steinert, C. (2017). Psychodynamic therapy meets evidence-based medicine: A systematic review using updated criteria. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(7), 648–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00155-8

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Anxiety disorders

- Stein, M. B., & Sareen, J. (2015). Generalized anxiety disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 373(21), 2059–2068. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1502514

- Thwaites, R., & Freeston, M. H. (2005). Safety-seeking behaviours: Fact or function? How can we clinically differentiate between safety behaviours and adaptive coping strategies across anxiety disorders? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465804001985

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203582015

The preceding article was solely written by the author named above. Any views and opinions expressed are not necessarily shared by GoodTherapy.org. Questions or concerns about the preceding article can be directed to the author or posted as a comment below.

Disclaimer: This content was automatically imported from a third-party source via RSS feed. The original source is: https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/anxiety-isnt-random-anxiety-as-a-signal/. xn--babytilbehr-pgb.com does not claim ownership of this content. All rights remain with the original publisher.